Around the time when Justin Trudeau announced his candidacy for leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, I remember seeing an article that claimed that he had a good chance because he had “spent time in the trenches” during the previous federal election campaign.

Around the time when Justin Trudeau announced his candidacy for leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, I remember seeing an article that claimed that he had a good chance because he had “spent time in the trenches” during the previous federal election campaign.Justin Trudeau in the trenches? Had he been embedded with Canadian forces in Afghanistan? How come I had not heard about it? I continued reading. Of course, Justin Trudeau has spent no more “time in the trenches” than I have. The writer was referring to his door-to-door campaigning in Montreal. Now, I realize that Montreal can get pretty cold, and that people aren’t always friendly to unsolicited visitors. But this hardly amounts to “time in the trenches.”

Military metaphors and the language of violent conflict are a ready source of clichés for journalists and bloggers. We have the “war on the car,” the “war on Christmas,” “patent wars” between Apple and Samsung, and even an alleged “war against boys” in the education system. It is commonplace to describe any dispute as a “battleground.” We often hear of the necessity to “open a new front” in some conflict. (This usually amounts to something like filing a motion in court.) Last week Bill Daly, deputy commissioner of the National Hockey League, made the ridiculous remark that the NHL’s demand to limit player contract lengths to five years would be “the hill we will die on.” Please. I understand that professional hockey is important to many people in this country, and if I were one of those people, I would certainly be very frustrated right now. But holding fast to your position in a negotiation is not remotely like a heroic martyrdom in battle, no matter how much money or whatever “principles” are at stake.

The appeal of exaggerated language is not hard to fathom. Leaders speak of “rallying the troops” and “fighting the good fight” because doing so is motivational. People need to feel that their actions matter, the consequences are significant, and that the conflict they’re engaged in is important. Journalists present rather banal disputes and legal contests as “battles” in an effort to gain and hold our attention. But not every conflict is worthy of a “fight to the death.” The stakes are not always high. Even in a zero-sum type of conflict where compromise is impossible and only one side can prevail, the consequences of both winning and losing can be less momentous than the participants believe. The passage of time has a way of making both wins and loses less important than they seem at present.

The overuse of military metaphors is tiresome, but that isn’t the most important reason to resist it. This form of language inflation has consequences. If a conflict is a “battle” or a “war,” then it follows that one’s opponents are “the enemy” (and perhaps “evil” as well.) If one side is the “victor” (who presumably is entitled to the spoils), then the “vanquished” side is shamed or humiliated. If the other party in a dispute is not just someone you happen to disagree with, or someone whose interests are opposed to yours, but an “enemy,” then that makes compromise much more challenging. It makes hearing their position more difficult, and opportunities for joint problem solving and mutual gain are likely to be overlooked.

Considering every disagreement, whether it is a civic dispute, a political difference, or a legal contest, as a “war” or “battle” is probably bad for your mental health, and maybe even detrimental to the public good. Violent conflicts with life-and-death consequences are taking place now in Afghanistan, Syria, and Congo, to mention only a few. Let’s not trivialize the experiences of people there by exaggerating the importance and severity of our own conflicts.

Can you quit a job, and yet still be fired? Can an employer fire employees even though they seem to have left the job of their own free will? These questions are not riddles or

Can you quit a job, and yet still be fired? Can an employer fire employees even though they seem to have left the job of their own free will? These questions are not riddles or

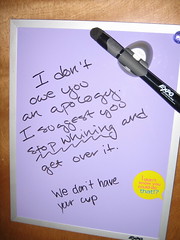

How to respond to the co-worker who criticizes your presentation, to your spouse who disapproves of the way you load the dishwasher, or to the random stranger who passes judgement on your parallel parking?

How to respond to the co-worker who criticizes your presentation, to your spouse who disapproves of the way you load the dishwasher, or to the random stranger who passes judgement on your parallel parking?

In my

In my  I just read a fascinating article in the New York Times:

I just read a fascinating article in the New York Times:

![NEUTRAL [- +] Which side are you?](http://farm1.staticflickr.com/79/223933153_b54a0fd53f_m.jpg)

Mediators typically hope that the negotiations they facilitate will be “win-win.” This means that each party, while not perhaps getting everything they want, will get something of value or importance – something that they would not necessarily have gained through a different kind of dispute resolution process. Mediators are encouraged to think broadly and help parties create value. To use a robust cliché, we try to help the parties think about how to make the pie bigger before we help them portion it out.

Mediators typically hope that the negotiations they facilitate will be “win-win.” This means that each party, while not perhaps getting everything they want, will get something of value or importance – something that they would not necessarily have gained through a different kind of dispute resolution process. Mediators are encouraged to think broadly and help parties create value. To use a robust cliché, we try to help the parties think about how to make the pie bigger before we help them portion it out.

Last week Forbes published a widely read article (over 15, 000 views) called “T

Last week Forbes published a widely read article (over 15, 000 views) called “T You may have heard that Tuesday night’s performance by the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall was abruptly halted because of a stubbornly loud and persistent cell phone. The orchestra was playing the final movement of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, considered by some to be one of the most emotionally rich and sublime pieces of music ever written. Towards the end, at the worst possible moment, the insistent plinking of the iphone “marimba” ringtone completely shattered the atmosphere. Alan Gilbert, the conductor of the Philharmonic, actually stopped the performance and glared at the offender until he managed to silence the phone. (You can read an amusing account of the evening

You may have heard that Tuesday night’s performance by the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall was abruptly halted because of a stubbornly loud and persistent cell phone. The orchestra was playing the final movement of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, considered by some to be one of the most emotionally rich and sublime pieces of music ever written. Towards the end, at the worst possible moment, the insistent plinking of the iphone “marimba” ringtone completely shattered the atmosphere. Alan Gilbert, the conductor of the Philharmonic, actually stopped the performance and glared at the offender until he managed to silence the phone. (You can read an amusing account of the evening